December 29, 2006

October 22, 2006

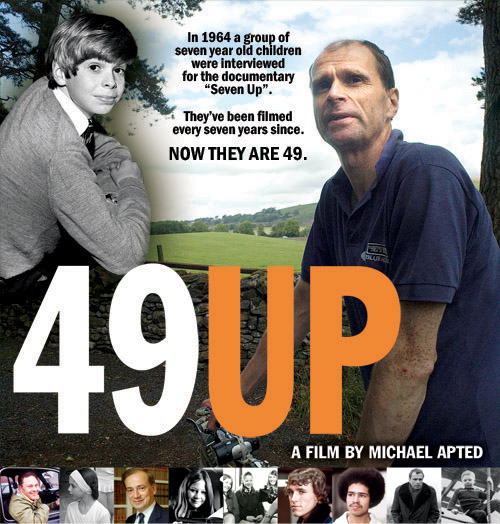

49 Up

Reviewed by Martin Tsai

Exploring the impact of class difference on the lives of 14 seven-year-old school children, the groundbreaking 1964 documentary Seven Up! became a cultural landmark in its native England when it first aired. Director Michael Apted has been documenting those lives ever since, following up on them every seven years with a new installment. Through the various films, viewers witness each participant’s innocent childhood, carefree adolescence, hard-fought adulthood, and painful midlife crisis.

The latest, 49 Up, is the first to hit American shores. The 12 subjects (two of the original 14 dropped out in their 20s) have all pretty much given up their lofty ambitions, reconciled with past troubles, and settled for life’s rewards on a relatively lesser scale. Juxtaposing current looks at the 12 with archival footage from previous installments, the film puts life – both theirs and ours – in perspective. It shows how one can turn from a chubby-faced child to a wrinkled grandparent quite literally in a flash.

John and Andrew went to the pre-prep school and predictably grew up to be barristers. Working-class Jackie and Sue went through jobs and marriages, and became single parents. Bruce showed an early sensitivity toward poverty and racial issues, and wound up teaching kids in Bangladesh. Tony failed at being a jockey in his youth and did a string of odd jobs. Nick transcended his early years on the farm and became a nuclear physicist in the States. Neil was unemployed and homeless throughout his 20s and 30s, and later recovered to become a district councilor. It’s mind-boggling to see how some of them remain essentially the same people and achieve their childhood goals, while others have weathered life and emerge completely different.

What started out as a commentary on the class system has morphed into something far more profound. No class is immune from failed aspirations, broken marriages and the joys of parenthood and grandparenthood. The film’s social commentary reaches even further beyond the lives of its subjects: As they move into posh suburbs or promised foreign lands, East Indian immigrants have taken over their old East End neighborhood.

The film is also no longer Apted’s. Feeling that the series has invaded their privacy and their dirty laundry has become water-cooler gossip, many participants start to take the reins of their own narratives by withholding information or questioning the voyeuristic nature of the project. Some of them pointedly accuse Apted of projecting his middle-class worldview onto the series, while others suspect an ulterior motive behind his questions.

Objectively, one can argue that Apted is in a way still projecting his own view in spite of his objects’ attempt to exert control over the depiction of their lives. The 65-year-old filmmaker is possibly facing the issue of mortality, and 49 Up seems to be putting more emphasis on children and family life. But it’s also possible that this entire generation has already fought its battles, and they now just want to live out the remainder of their lives in comfort and contentment.

There are few documentaries or even dramatic films that are able to articulate life quite like 49 Up. This is not just a slice of life, but life in its entirety. Encompassing class, money, marriage, sex and parenthood, the film tells the story of the post-war, baby-boomer generation like few others could. In the age of the so-called reality television when people mug for the camera and blow the most insignificant thing out of proportion, 49 Up reminds us that pure, unadulterated reality is truly quite a spectacle to behold.

Reprinted from EmanuelLevy.com. © Copyright 2006 Martin Tsai. All rights reserved.

October 14, 2006

Marie Antoinette press conference at the 44th New York Film Festival

Photo by Martin Tsai. Marie Antoinette director Sofia Coppola and star Kirsten Dunst at the Alice Tully Hall in New York City on Oct. 13.

Photo by Martin Tsai. Marie Antoinette director Sofia Coppola and star Kirsten Dunst at the Alice Tully Hall in New York City on Oct. 13.

By Martin Tsai

“I didn’t know very much about her, except for this iconic decadent evil queen. When I started reading about her, I was struck by how young she was. She was this 14-year-old kid. I read about the side that is a real person, who had a lot of sympathetic qualities as well as flaws,” Sofia Coppola said of Marie Antoinette. “I wanted to make an impressionistic view of her. I wanted all the music to reflect emotions the character was having at that time. I wanted to take the adults in the court and the music of the period and then contrast that with the world of the teenagers and the more contemporary music that shows the energy.”

Since its debut at the Cannes Film Festival, Coppola’s Marie Antoinette has met a lukewarm reception in France. But the film gets a second chance in the States, where it premieres at the prestigious New York Film Festival. At the press conference, Coppola seemed less interested in talking about her use of contemporary music in a period piece. She became more engaging and articulate only when she had to defend some of her historical choices rather than artistic ones.

“There are so many elements, we couldn’t put every single thing in … We couldn’t go into every area because it was an impressionistic portrait,” Coppola responded when journalists asked her why she chose not to show Marie Antoinette’s decapitation and glossed over her illiteracy.

“The story after they leave Versailles is a long period of 10 years in prison and a long trial and then escape,” she said. “We weren’t making a miniseries so I couldn’t tell that whole story. I decided to focus on the years in Versailles prior to her departure, to show that she evolved and became a woman.”

Kirsten Dunst, who plays the title role, finds Coppola’s method is more rewarding to her as an actress than the textbook approach. “Already I knew this would be something different from how I would normally approach a historical figure. (Coppola) forced me to look at her in such a personal way that I had never looked at somebody in history before. There are so many facets about Marie Antoinette. I could have the freedom of my own in trying to find the essence of her, not judge her, and understand her point of view as a woman at whatever stage she might be in.”

Coppola said it was thrilling for the cast and crew to be able to film on location in Versailles, especially in the museum’s private areas. The only issue was for her producer Ross Katz to schedule the filming, since the museum is open to the public most of the time.

“It was a very scary thing going to France and not knowing we would have permission to shoot in Versailles,” Katz said. “After one meeting with the current head of Versailles – the director general of the palace – he said that he was going to open the gates to the palace so we would be able to tell the interior life of the character. From that point on they were with us every day to film at a place that has spoken to millions of people.”

© Copyright 2006 Martin Tsai. All rights reserved.

October 10, 2006

Triad Election press conference at the 44th New York Film Festival

These Girls press conference at the 44th New York Film Festival

October 09, 2006

October 07, 2006

Inland Empire press conference at the 44th New York Film Festival

Photo by Martin Tsai. Inland Empire stars Justin Theroux, Laura Dern and director David Lynch at the Alice Tully Hall in New York City on Oct. 6.

Photo by Martin Tsai. Inland Empire stars Justin Theroux, Laura Dern and director David Lynch at the Alice Tully Hall in New York City on Oct. 6.

Photo by Martin Tsai. Inland Empire director David Lynch at the Alice Tully Hall in New York City on Oct. 6.

Photo by Martin Tsai. Inland Empire director David Lynch at the Alice Tully Hall in New York City on Oct. 6.

Story to follow.

© Copyright 2006 Martin Tsai. All rights reserved.

Falling press conference at the 44th New York Film Festival

October 05, 2006

Terry Gilliam at IFC Center

Photo courtesy of Bobby Miller. Martin Tsai and director Terry Gilliam at the IFC Center in New York City on Oct. 4.

Photo courtesy of Bobby Miller. Martin Tsai and director Terry Gilliam at the IFC Center in New York City on Oct. 4.

Volver press conference at the 44th New York Film Festival

Photo by Martin Tsai. Film Society of Lincoln Center program director Richard Peña, Volver director Pedro Almodóvar, star Penélope Cruz and executive producer Agustín Almodóvar at the Walter Reade Theater in New York City on Oct. 4.

Photo by Martin Tsai. Film Society of Lincoln Center program director Richard Peña, Volver director Pedro Almodóvar, star Penélope Cruz and executive producer Agustín Almodóvar at the Walter Reade Theater in New York City on Oct. 4.

By Martin Tsai

When asked how he has changed over the years, Pedro Almodóvar replied: “My hair is more white.”

Truth be told, the Spanish auteur once branded by critics as an enfant terrible has mellowed quite a bit over the years. His staple drag queens, druggies and flamboyant gay men are completely absent in Volver.

Penélope Cruz, who worked with him seven years ago on All About My Mother and recently on Volver, said that “Maybe the thing I found a little different in this shoot was he was giving this feeling of peace to everyone on the set. He was very wistful, so relaxed. I care a lot about him so I was happy to see him so happy during the shoot.”

Almodóvar said Volver is about – among other things – maternity and mortality. The story is about a mother reappearing to her two daughters years after her death. It features a clip of Luchino Visconti’s 1951 Bellissima, and Almodóvar thinks that Anna Magnani from that film embodies “the iconography of housewives and mothers in cinema.” In both films, the mothers feel threatened by their more beautiful daughters. Almodóvar said that he isn’t someone who dreams or thinks a lot about his childhood, and didn’t really use his childhood experiences as subjects of his films until the last three or four years. He started to look at things from his childhood more positively – such as the women who raised him – perhaps due to his increasing awareness of his own mortality.

The filming of Volver took Almodóvar back to his birthplace, Castilla-La Mancha, a place for which he once had much contempt. “It gave me the reconciliation I needed,” he said, “because I didn’t like to think about my childhood.” He said that it was the last place on earth he wanted to live, because it was a region that was very reactionary, extremely conservative, and really quite macho in many ways. According to his eyes as a child, the region was against sensuality.

“ ‘Volver’ is a title with many meanings,” Almodóvar explains. “One of the more important things for me was to come back, to return. It was going back to my roots. It was incredible. It was something that I didn’t expect that I’d feel during the shooting. It was to go back to the same place where I was born, where I lived my first eight years, the place where I saw my mother – not in the same way in the movie – and basically how strong she was. I also come back to work with Carmen Maura. We didn’t work together in the last 18 years. And I also go back to work with Penélope. The last time we were here it was seven years ago. Also you know Volver is the title of the CD by Carlos Gardel. ‘Volver’ means also the passing of time … There are some very powerful meanings with this title.”

© Copyright 2006 Martin Tsai. All rights reserved.

49 Up press conference at the 44th New York Film Festival

Photo by Martin Tsai. 49 Up director Michael Apted, Tony Walker and Film Society of Lincoln Center program director Richard Peña at the Alice Tully Hall in New York City on Oct. 4.

Photo by Martin Tsai. 49 Up director Michael Apted, Tony Walker and Film Society of Lincoln Center program director Richard Peña at the Alice Tully Hall in New York City on Oct. 4.

By Martin Tsai

In 1946, Michael Apted got a glimpse of the lives of 14 seven year olds when he worked as an assistant on the landmark British documentary Seven Up! He has been documenting those lives ever since, following up on them every seven years with a new installment. The latest, 49 Up, also happens to be the first to hit American shores.

Apted said the series is the most important he has ever done, and its success has launched his career. His subjects also find themselves household names in England and experience the downside of celebrity. Tony Walker, one of the subjects, said he was surprised when someone stopped him in Central Park and sought his autograph.

“A lot of people had asked me about my marriage problems, which I can honestly say is intrusive. But I accept that because that’s what was happening in that particular time,” Walker said. “That’s why I give a true reflection to Michael. He wanted my honesty, so I try to give him a truthful personal interview.”

With the exception of two, all of the subjects continue to participate in the series. But some of them are also quite cautious about the series’ presentation of them and now demand editorial control. The new film includes a scene in which the subject Jackie Bassett frankly questions Apted’s ulterior motive.

“I’ve always felt that documentaries sort of get off the hook of it. There are some pure depictional problems in that I think documentaries can be as manipulative as anything,” Apted said. “And I always have been aware. I’ve tried to correct it in some ways. I’ve always been trying to avoid projecting my own middle-class insecurities.”

Apted said he does accommodate his subjects so that he can go back and interview them again. For his part, he doesn’t revisit the older films before making a new installment or ask follow-up questions during the interviews.

“They each have a different voice. They each have a different tone to them,” he said. “It is kind of surprising. That’s one of the adventures of doing it. You never know what it’s going to be about until you put it together. So the criterion is what is happening with them now rather than making it a self-fulfilling prophecy. It’s a powerful thing to do, but being able to just think about it is a good exercise to do instead of retread the old stuff just so we can get some answers and make some nice cuts.”

The director said the project began as a reflection on the English class system and the generation that was born in 1956, but now the system isn’t as claustrophobic or suffocating. It has taken him a while to realize that he isn’t making a political film, and there are more personal and universal ramifications like relationships, children, money and sex.

“The real kind of tragedy for Tony and everyone else is that they cannot reinvent themselves. There they are,” Apted said. “I would like to see what I was like when I was seven years old, but if I got caught on the film you would have seen that I was a shy, reserved, cowardly boy … I could do a revisionist history of my life, and I had this vision of me as a seven-year-old boy that is total bullshit that probably you would see as sort of an aggressive alpha male who would go on to make a Bond film.”

© Copyright 2006 Martin Tsai. All rights reserved.

September 28, 2006

The Queen press conference at the 44th New York Film Festival

Photo by Martin Tsai. The Queen director Stephen Frears outside the Walter Reade Theater in New York City on Sept. 25.

Photo by Martin Tsai. The Queen director Stephen Frears outside the Walter Reade Theater in New York City on Sept. 25.

Photo by Martin Tsai. Film Society of Lincoln Center program director Richard Peña, The Queen star James Cromwell, director Stephen Frears, star Helen Mirren, writer Peter Morgan and producer Andy Harries at the Walter Reade Theater in New York City on Sept. 25.

Photo by Martin Tsai. Film Society of Lincoln Center program director Richard Peña, The Queen star James Cromwell, director Stephen Frears, star Helen Mirren, writer Peter Morgan and producer Andy Harries at the Walter Reade Theater in New York City on Sept. 25.

By Martin Tsai

“If you are British, the royal family is very complicated and they are laughed at nonstop. They are in many respects quite ridiculous. On the other hand, you can’t make the film from many positions that don’t contain sympathy for or curiosity about the sort of human beings underneath it all,” director Stephen Frears said. “What’s shocking and controversial about this film is that it takes them seriously.”

Frears’ new film The Queen, which just opened the 44th New York Film Festival, focuses on how the British royal family coped in the aftermath of Princess Diana’s death and the relationship between Queen Elizabeth II and British Prime Minister Tony Blair at the height of his popularity. Though much of the film draws from actual events, screenwriter Peter Morgan imagines the goings on behind the scenes.

“The relationship between the queen and the prime minister has always been the thing that sort of piqued the interest for me,” Morgan said. “The fact that they are in a room together and the fact of them talking about politics or all these meaningless conversations, it immediately has constitutional resonance for me as an Englishman – the idea of putting that kind of power in the same room and the sort of private audience they might have.”

The events depicted here took place nearly a decade ago, and the British public’s opinion of Tony Blair has changed considerably. Although depicting him mostly as a sympathetic character, Morgan illustrates the “conservatizing of Tony Blair.”

“We couldn’t do a hatchet job on him if we wanted to because this was sort of his finest hour,” Morgan said. “For the film to portray him badly would just be irresponsible and inaccurate. He conducted himself extraordinarily well. Having said that, we did look for opportunities to try and express some of that.”

In preparation for the title role, actress Helen Mirren said she read a lot, looked at portraits, watched videos and was lucky to have a wonderful voice coach. “I was very drawn to the queen as a young girl, and spent most of my time researching and watching things from when she was young, before she ever had any slight ideas that she would be the queen. I thought that would probably reveal the true character and her true personality.”

Frears said that his empathy for the queen has probably deepened because of Mirren’s performance in the title role.

Mirren allowed, “Actually, I’m not really a very political person. I think a lot about politics, but I don’t mix with politics. I was happy about Labor coming into power, because it was a change and the change was very much needed at that time in Britain. It was exciting and interesting to view what might be coming next. But I am very cynical about politicians, all of them. I am holding out no great hopes for utopia or a new day in Britain. But in terms of it playing into my occupation, I think more of my feelings toward monarchy play into that. I grew up in a vehemently anti-monarchy family, and I embraced these ideas and frowned on the royal family for a very long time – until relatively recently when I’ve mellowed somewhat."

© Copyright 2006 Martin Tsai. All rights reserved.

The Go Master press conference at the 44th New York Film Festival

September 26, 2006

Mafioso press conference at the 44th New York Film Festival

Photo by Martin Tsai. Film Society of Lincoln Center associate director of programming Kent Jones; Carla Del Poggio, widow of Mafioso director Alberto Lattuada; and translator Chiara Carfi at the Walter Reade Theater in New York City on Sept. 25.

Photo by Martin Tsai. Film Society of Lincoln Center associate director of programming Kent Jones; Carla Del Poggio, widow of Mafioso director Alberto Lattuada; and translator Chiara Carfi at the Walter Reade Theater in New York City on Sept. 25.

Story to follow.

© Copyright 2006 Martin Tsai. All rights reserved.

September 25, 2006

Little Children

Directed by Todd Field Starring Kate Winslet and Patrick Wilson

Directed by Todd Field Starring Kate Winslet and Patrick Wilson

Reviewed by Martin Tsai

Based on Tom Perrotta’s New York Times bestseller, Todd Field’s long-awaited follow up to his Oscar-nominated In the Bedroom has the potential to be something really magnificent but never quite gets there. To be fair, Little Children is indeed lovely. But a film belonging to this particular breed of exposé on suburban discontent inevitably recalls the likes of The Ice Storm, American Beauty and Happiness even if it doesn’t pale by comparison.

Residents of bucolic East Wyndam, Mass. suddenly get hysterical over a recently-released sex offender (Jackie Earle Haley) moving into the neighborhood. But this frenzy serves only as backdrop to the illicit affair between the overeducated homemaker Sarah (Kate Winslet) and the ex-jock stay-at-home-dad Brad (Patrick Wilson). Sarah must contend with a bratty daughter (Sadie Goldstein) who refuses to sit in her car seat and a husband (Gregg Edelman) who masturbates to Internet porn. Brad’s wife (Jennifer Connelly) highlights unnecessary magazine subscriptions on his monthly credit-card bill. Among the parents who take their kids to the playground and the pool each day, Sarah and Brad are seemingly the only kindred spirits and quickly gravitate toward each other.

Perrotta’s novels share an unmistakable satirical deadpan, and Jim Taylor did a stellar job fleshing that out with his whip-smart screenplay for Election. While Little Children is occasionally very funny, the overall detached and contemplative tone – due to the third-person narration and Field’s direction – strips away the uniqueness of the source material and renders the film somewhat derivative of American Beauty. Little Children also feels a bit telegraphed, with breadcrumb trail foreshadowing all the way to its neatly pieced-together conclusion.

With that said, Field’s new film is still quite a worthwhile experience due to its complex characterizations and its moral ambiguity. The subplot involving Haley’s sex offender Ronnie truly stands out here, to the extent that it eclipses the central plot revolving around Sarah and Brad. In the film’s best-executed scene, Ronnie goes swimming and sightings of him quickly send a wave of panic across the pool. In another powerful scene, his overbearing mother (Phyllis Somerville) confronts a disgraced ex-cop Larry (Noah Emmerich) who has taken it upon himself to chase Ronnie out of the neighborhood. It’s fascinating how the most reviled characters here completely captivate viewers while the readily identifiable protagonists’ midlife crises seem frivolous by contrast.

© Copyright 2006 Martin Tsai. All rights reserved.

Marie Antoinette

Directed by Sofia Coppola Starring Kirsten Dunst

Directed by Sofia Coppola Starring Kirsten Dunst

Reviewed by Martin Tsai

Sofia Coppola’s New Wavesque Marie Antoinette gives a rare sympathetic glimpse at the rise and fall of the infamous French queen. The kind of public ridicule Coppola endured after making her acting debut in The Godfather: Part III most likely helps this daughter of a Hollywood monarch identify with Antoinette’s story of a clueless royal reviled by her subjects. As if cautioning the audience on her through-the-rose-colored-glasses subjectivity, Coppola here adopts a predominantly cotton-candy pink mise en scène.

First seen here as a giggling blonde, Kirsten Dunst’s Marie must leave all her Austrian connections (puppy included) behind at age 14 for France to marry Louis-Auguste (Jason Schwartzman), the gawky grandson of King Louis XV (Rip Torn). With international relations on the line, Marie quickly faces the daunting task of producing an heir with the sexually unresponsive Louis-Auguste in order to prevent the annulment of her marriage – a feat that would eventually take her seven years to accomplish. Meanwhile, she finds consolation in a life of excess involving fashion, food and parties to relieve her sexual draught, especially with the lack of adult supervision after Louis XVI’s coronation. With the royalty’s lavish lifestyle and the country’s contribution to the American Revolutionary War, the French people become embittered about the national debt and their own revolution is imminent.

Reminiscent of The Virgin Suicides, Coppola puts together several visually poetic montages – many overflowing with silk, bonbons and gâteaux. Unfortunately, these vignettes seem to really work against the film’s true strength in illustrating Marie’s insular existence. The most memorable scene is a silent shot of a stoic Marie blankly looking out from the balcony, with the telephoto lens rapidly pulling back to reveal the enormity of the palace that represents the oppression she must bear.

Coppola manages to further undermine her own effort by going off on a tangent with Marie’s alleged affair with Swedish Count Alex von Fersen (Jamie Dornan), whom the film characterizes as some kind of a manwhore. Curiously, the co-writer/director leaves out Marie’s imprisonment and decapitation by guillotine, which would be devastating here given Coppola’s sympathetic treatment.

The most notable gimmick in Marie Antoinette is its use of a contemporary soundtrack consisting of bands like The Cure, The Strokes and Air. The film’s attempt at the New Wave feel loses its momentum whenever Coppola half-heartedly trades rock songs and handheld camera for classical music and stately cinematography. This novel concept works well with some of the montages, but becomes laughable when Coppola employs it diegetically – particularly in a ballroom scene. Any of the film’s attempts at authenticity are futile at that point.

© Copyright 2006 Martin Tsai. All rights reserved.

September 23, 2006

Little Children press conference at the 44th New York Film Festival

Photo by Martin Tsai. Film Society of Lincoln Center program director Richard Peña, Little Children director Todd Field, stars Kate Winslet, Patrick Wilson, Noah Emmerich and novelist Tom Perrotta at the Walter Reade Theater in New York City on Sept. 22.

Photo by Martin Tsai. Film Society of Lincoln Center program director Richard Peña, Little Children director Todd Field, stars Kate Winslet, Patrick Wilson, Noah Emmerich and novelist Tom Perrotta at the Walter Reade Theater in New York City on Sept. 22.

By Martin Tsai

“Family life is fascinating to me because that’s what I’ve known for a very long time and because there is so much drama and melodrama in family life. Things that happen in my household are mind-boggling to me,” Todd Field said. The director/co-writer of the Oscar-nominated In the Bedroom returns after a five-year hiatus with the big-screen adaptation of Tom Perrotta’s bestseller Little Children. With these two films, Field has already established a knack for the domestic relations milieu. Set in a suburb startled by the recent arrival of a newly-released sex offender, Field’s latest effort focuses on the unraveling lives of several families.

“There have been many fine movies of late that deal with – specifically in fine detail – characters with this kind of behavior as a whole film, and those are hard films for me. I have three children and I don’t really want to see that sort of thing,” Field said. “I always looked for reasons to say ‘no, I’m not gonna do this’ and I couldn’t. Its voice was so strong and it affected me in a way that I probably didn’t fully understand.”

The complex drama also attracted Kate Winslet in spite of the fact that she too grappled with its subject matter. “I was initially very hesitant to even read it, because I knew that there was this sex-offender character within the piece. One would just have an extremely powerful allergic reaction to that initially as an actor,” she said. “And then I knew it was Todd whom I had admired for a long time and also Tom. After Election and etc., I was very aware of the book. Then I read the script, and I not only really, really loved the script, the story and the dialogue, it was just so seamless somehow.”

Field credits Perrotta’s observant characterizations, as well as his “very sharp, very funny, and also appropriately kind” writing voice that has eased his qualms about the controversial subject matter. “Part of what struck me when I read Tom’s book about this character is that he is everybody’s nightmare. He is a receptacle to this whole form of McCarthyism by this community based on hearsay, and based on one man’s accusations in which this entire community turns against this man and his mother. We don’t really know what he’s done. We know there are things he’s battling with, but he is also in many ways more upfront about what his problems are than these other characters.”

The film features the relatively unknown Patrick Wilson and Jackie Earle Haley in two of its meatiest roles. Haley won the challenging part of sex offender Ronnie after an equally unconventional audition, and Winslet also gave him a raving recommendation. “When you think about a role like that, probably many people would have the same five ideas, and I heard them over and over and they were all good actors. But it was important that whoever played this role be somebody who wasn’t on that top-of-the-head list, but I had no idea who that would be,” Field said. “I came back to the hotel one night and there was a tape sitting there. It was from Jackie Earle Haley. So now he had gotten his hands, I don’t know how, on a very, very early draft of the script. He had made a short 20-minute film as this character. It was rather daunting actually, because Jackie for the last several years has been making his living as a regional commercial director. So you get tracking shots in this very involved thing. And I thought, oh Lord, this guy can really direct!”

Perrotta said the actors help fill in many blanks in the script, especially when many of their characters’ backstories in the book aren’t part of the shooting script. “There’s a lot of the book that just by default has to get lost. It’s a 350-page book with seven main characters. I think the interesting issue for Todd and I when we were writing the script was how to deal with the past and the whole background. The book actually begins with character sketches, and you really know a lot about who these characters are by the time you meet them,” he said. “What happens is somehow actors in their physical presence imply a past. I was surprised how little that stuff that was essential in the novel needs to be there. There was this ghostly presence of the past that just lingers around these characters.”

Despite all the acclaim that In the Bedroom received, Field said he had a tough time getting another film off the ground until he came across Little Children. Conveniently, his producers had already collaborated with Perrotta on Election which gave him first dibs on the novel.

“The strange thing for me is, you make a film, it goes out, and has a life of its own completely separate from you. And I think there’s a natural assumption, I certainly have this, that it will be easier to make another film. That simply isn’t true,” he said. “I spent five years trying to get another film going. I’ve not been able to get backing for kitchen-sink dramas. I’ve written scripts that no one wants to make. When I found this book of Tom’s, I wanted to make it like I wanted to make other things. I was just fortunate to have somebody that said ‘yes, let’s make the film’.”

© Copyright 2006 Martin Tsai. All rights reserved.

September 20, 2006

Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple

Reviewed by Martin Tsai

The 1978 mass murder/suicide involving more than 900 Peoples Temple members in Guyana – hundreds of them children – remains one of the most chilling examples of the religious cult phenomenon. Featuring newly procured home movies, photos, and voice recordings, as well as interviews with the survivors, Stanley Nelson’s documentary Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple serves as a chilling cautionary tale on the dangers of blind-faith fanaticism.

Reverend Jim Jones was an outsider during his formative years in 1930s’ Indiana, which was then a stronghold of the Ku Klux Klan. At this early age, he found a sense of belonging at church services and sympathized with the plight of oppressed black people. Interviews with his childhood peers reveal Jones’ unorthodox early fascination with religion: He would kill small pets and perform mock funerals for fun.

Jones began building Peoples Temple in 1950s’ Indianapolis. Survivors describe the electrifying services where church members sang and danced in the aisles. The film also features several recordings of the church choir performing. “Peoples Temple really was a black church. It was led by a white minister, but in terms of the worship service, commitment to the social gospel and its membership, it functioned completely like a black church,” an interviewee recalls.

Feeling that Indianapolis was too racist for his ideal of a racially-integrated congregation, Jones moved the church to rural California in 1965. Gradually, he convinced members to surrender their salaries and life savings as contributions to the construction of a self-contained utopia.

As Peoples Temple grew to thousands strong, Jones lent support to various causes by mobilizing his followers to attend various rallies and demonstrations. He gained tremendous political clout in San Francisco during the mid-1970s, when Mayor George Moscone appointed him to be Chairman of the City Housing Authority. Meanwhile, Jones grew increasingly paranoid as his substance abuse problems worsened.

In 1977, on the eve of a magazine exposé, in which defectors from Peoples Temple detailed physical abuses at the church, Jones and nearly 1,000 members fled to a settlement in Guyana, where he was in total control of all aspects of the people’s lives. When Representative Leo Ryan and several journalists visited Jonestown in 1978 at the urging of concerned relatives, Jones ordered the assassinations of Ryan and the rest of the delegation, as they were about to board the plane to return to the U.S.

Obviously knowing that this horrific act would sound the death knell for him and his utopian dream, Jones directed the poisoning of nearly everyone in the compound with cyanide-laced Kool-Aid.

Veteran documentarian Nelson here constructs a fairly standard film. Various interviewees, mostly survivors or relatives of deceased Peoples Temple members, lend narration to the archival photographs, newspaper clippings, and never-before-seen footage.

However, Jones remains somewhat of an enigma throughout the documentary. Audio interviews and sermons, as well as news footage featuring the charismatic pied piper, offer little insight, and viewers must piece together his mental state based on fragmented descriptions supplied in the interviews. The most chilling piece of evidence here is a voice recording made during the mass murder/suicide, when Jones urged the killing of children at Jonestown.

The 85-minute documentary seems to be on the short side. Nelson carefully constructs the first half, which details the rise of Peoples Temple. Then the film rushes through its more disturbing second half, as survivors describe their own ordeals of unwanted sexual advances without necessarily establishing the big-picture magnitude of Jones’ corruptions and abuses.

Nelson does not address the conspiracy theories that have surfaced since the disastrous event, especially the alleged involvement of the CIA. He also fails to touch on the fact that 5,000 pages from a government investigation remain classified to this day.

Judging from recent headlines on religious and polygamy sects, the story of Jonestown is certainly pertinent today with some universal notes as well. But Nelson doesn’t really provide the perspective that would come from delving deeper into the scale and the modern-day relevance of the Jonestown tragedy.

Reprinted from EmanuelLevy.com. © Copyright 2006 Martin Tsai. All rights reserved.

September 16, 2006

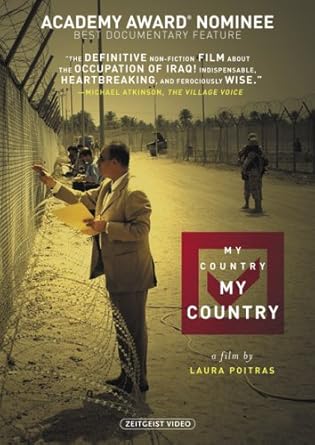

My Country, My Country

Directed by Laura Poitras

Directed by Laura Poitras

Reviewed by Martin Tsai

A documentary on Iraq’s 2005 election, Laura Poitras’ My Country, My Country presents a viewpoint too rarely seen in the slew of news coverage and other documentaries on the war that ravaged nation. Unlike Gunner Palace, The War Tapes and The Ground Truth – which all spotlight American troops – Poitras’ film follows the six-month campaign trail of a Sunni candidate running for the Governorate Council of Baghdad.

An all-around nice guy, Dr. Riyadh goes out of his way for patients at the Adhamiya Free Medical Clinic, even lending money to a woman whose husband is unemployed. Although he is critical of American secularism, Riyadh believes that it's crucial for his fellow Sunnis to participate in the election so they can have their say in the all-important drafting of the constitution.

Chaos is still ubiquitous in Baghdad two years after the U.S. invasion, when the docu is set. There’s no water or electricity as shootings and bombings continue. At the Abu Ghraib Prison, an inmate has stayed for over a year without getting a hearing, while another is only nine years old. Inspecting the prison, Riyadh can only shrug his shoulders and say to the grumpy inmates: “We’re an occupied country with a puppet government. What do you expect?”

Just three months before the election, the U.S.-led Fallujah offensive leads to the decision by Riyadh’s Iraqi Islamic Party to withdraw all of its candidates. With the deadline for withdrawal already past and the ballots printed, Riyadh continues to rally the Sunnis’ vote amid much resistance. One of his family members says: “Politics are not good for you. You do more good as a doctor for us and other people.”

My Country is a possibly unprecedented story, told almost entirely from the Iraqi perspective. Riyadh’s tale is fascinating, especially when seen alongside those of the U.S. soldiers related in the numerous other documentaries on the Iraq War. This engrossing film unfolds with captivating dramatic tension, which builds all the way up to the climactic election day.

Riyadh’s journey allows Poitras tremendous access into areas mostly untapped by Western journalists, such as a meeting of Iraqi Islamic Party members. She counterbalances Riyadh’s views by featuring vignettes involving U.S. military personnel, U.N. officials, Australian security subcontractors, Kurdish militia, etc.

The documentary still appears to be somewhat one-sided since even the seemingly pro-Bush Kurds criticize the fact that things are not getting better under the U.S. occupation. In one very telling digression, a U.S. official tells the Iraqi election police that they have “the front row of one of the best shows that are gonna be in the world.” Then an election policeman with a puzzled look raises his hand and asks “Election for show?” Riyadh in another scene asks someone whom she’d vote for, and she flatly replies “Saddam Hussein”.

The film comes off a bit like Secret Ballot, due to its focus on Riyadh’s tireless promotion of democracy. Unfortunately, My Country fails to fully illustrate its political backdrop. The docu clocks in at only 90 minutes, so there would seem to have been ample room for a more expansive take. Poitras doesn’t really explain where the Sunnis fit in relation to the Kurds, the Shia, the Arabs and the Turks. Another problem is the film's conclusion, which could be somewhat misleading to viewers who haven't closely follow the news.

Even so, despite shortcomings, My Country is essential in venturing into new fertile grounds that arguably no journalists or filmmakers have previously explored.

Reprinted from EmanuelLevy.com. © Copyright 2006 Martin Tsai. All rights reserved.

August 11, 2006

Three Times

Directed by Hou Hsiao-hsien Starring Shu Qi and Chang Chen

Reviewed by Martin Tsai

If you haven't seen Flowers of Shanghai and Taiwanese auteur Hou Hsiao-hsien's other movies when screened in Seattle, Three Times serves as a fitting introduction to his body of work. Indeed, you could call it Hou Hsiao-hsien for Dummies. Set in three different periods, this triptych about love, time, and fate encapsulates the moods and preoccupations that have inspired him throughout his career. In each chapter, Chang Chen (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon) and Shu Qi (The Transporter) portray three different couples, each pair with a unique dynamic reflecting the era.

A reminiscence about the simpler times of Hou's youth, the 1966-set "A Time for Love" follows a lovesick young man as he searches for a demure billiards parlor attendant during his military leave. Revolving around a 1911 brothel (à la Flowers), the silent chamber drama "A Time for Freedom" recounts the hopeless affair between a courtesan and a married revolutionary whose principles compel him to reject concubinage. In the vein of Goodbye South, Goodbye and Millennium Mambo, the fluorescent-colored "A Time for Youth" explores the fleeting physical intimacy shared by two soulless Gen-Y'ers in an emotionally vacuous 2005, when everyone is venting discontent via cell phone rants, text messages, and e-mail.

Through repetitions and variations, Hou again explores how the shifting times may ripple the surface of life, but not our deeper need for bonding. Each of the three stories is a mini-masterpiece in its own right, as we see innocence, doom, and desperation played out. Each segment has its own rhythm and visual vocabulary: slow motion for 1966, fades for 1911, and tracking shots for 2005.

For those who've previously complained about Hou being too slow and austere, the bite-sized structure helps make Three Times more digestible. It may also send viewers to their DVD players with new insight regarding Hou's back catalog. From this perspective, even more politically charged works such as City of Sadness or The Puppetmaster appear to be portraits of a people adapting to different historical circumstances. And while Three Times can be seen "only" as a collection of love stories, they may add up to possibly the definitive treatment of Taiwanese life—today, yesterday, and the day before that.

Reprinted from Seattle Weekly. © Copyright 2006 Martin Tsai. All rights reserved.

July 12, 2006

June 30, 2006

The Hidden Blade

Directed by Yôji Yamada Starring Masatoshi Nagase

Directed by Yôji Yamada Starring Masatoshi Nagase

Reviewed by Martin Tsai

Don't be fooled by the title—Blade isn't the sort of Zatoichi variant it suggests. Rather, it's a revisionist and demystifying samurai saga. In 1861, at the end of the Japanese feudal era, the last samurai are clumsily adapting Western artillery and military formations without the assistance of Tom Cruise. Disgraced since his father's hara-kiri, Katagiri (Masatoshi Nagase of Mystery Train) impetuously rescues his former maid (Takako Matsu) from an abusive marriage, then dutifully abides by the caste system to suppress his affections for her. Meanwhile, he must prove his own innocence by dueling with a school pal accused of treason. Devoid of action until the climactic showdown, Blade is a stately yarn with slow-burn tension and heartwarming romance. But director Yôji Yamada already made the shogun equivalent of Unforgiven with the Oscar-nominated The Twilight Samurai. Though both are adaptations of Shuuhei Fujisawa novels, this follow-up pales slightly in comparison.

Reprinted from Seattle Weekly. © Copyright 2006 Martin Tsai. All rights reserved.

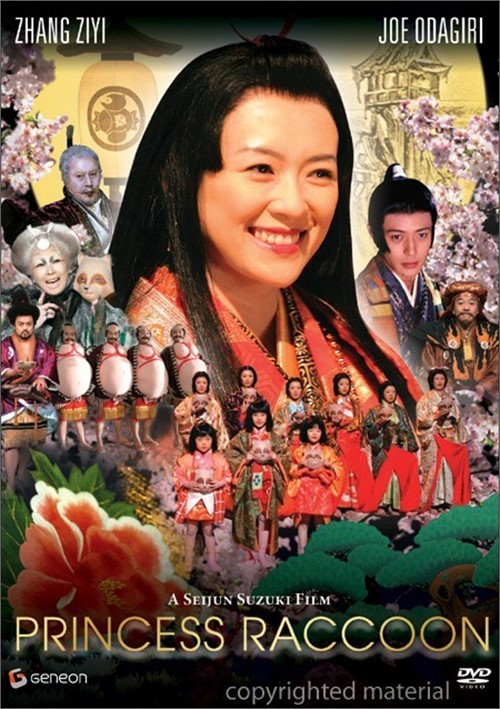

Princess Raccoon

Directed by Seijun Suzuki Starring Ziyi Zhang and Jô Odagiri

Directed by Seijun Suzuki Starring Ziyi Zhang and Jô Odagiri

Reviewed by Martin Tsai

The Japanese studio system banished him for a decade for making such delirium-addled B-movie classics as Tokyo Drifter and Branded to Kill, but 82-year-old Seijun Suzuki is still as bizarre and irreverent as ever. Raccoon is the seemingly timeless star-crossed romance between a royal raccoon (Ziyi Zhang) and a human prince (Jô Odagiri of Bright Future), exiled for fear that he would supplant his father as the fairest of them all. With Suzuki at the wheel, it's The Umbrellas of Cherbourg with kimonos and psychedelia. The film is a pastiche of Japanese opera, Greek tragedy, and French new wave. Like a continuity editor's worst nightmare, its mise-en-scène alternates inexplicably between theatrical stage, naturalistic exterior, and scroll-painting-superimposed blue screen—sometimes all within the same scene! The musical repertoire likewise covers as many genres as a season of American Idol. Ultimately, Raccoon demands and rewards the total suspension of disbelief. Its incongruous storytelling style takes some getting used to, but beneath lies a mischievously droll and sweet fable that'll leave you with a beaming smile.

Reprinted from Seattle Weekly. © Copyright 2006 Martin Tsai. All rights reserved.

April 02, 2006

Heading South

Directed by Laurent Cantet Starring Charlotte Rampling

Reviewed by Martin Tsai

Colonialist attitudes are still prevalent in the West even as actual colonies become a thing of the past. From politics to entertainment, the portrayal of foreignism variously conjures up exoticism, mysticism, pity, or fear. Laurent Cantet’s Vers le sud confronts these reflexive notions among its affluent protagonists and, by extension, its audience. Set in 1978, the film explores sex tourism in Haiti during the last days of the Duvalier. Sex-starved North American women of a certain age flock to the country for hot summer flings. They might not be exceptionally attractive by our ageist standards, but in Haiti they effortlessly score the objects of their desires simply by virtue of being atop the class hierarchy. Through conversations and interactions, their ignorance, stereotyping, objectification and hypocrisy vis-à-vis the locals casually emerge.

“At home black guys don’t interest me. It’s different here because they are closer to nature,” says Ellen (Charlotte Rampling), an acid-tongued 55-year-old Wellesley professor who has made annual trips there for six years . She takes up with the stunning and charismatic Legba (Ménothy Cesar), and chastises another tourist for dressing him like “black guys in Harlem.” Little does Ellen know that beneath the façade of an innocent island youth, Legba leads a dangerous life that embodies the worst stereotypes she has projected onto African Americans. Given her background and stature, her decidedly un-P.C. assertions regarding the locals threaten to take viewers aback. Most films in the West that involve foreignism simply gloss over this colonialist mindset and unwittingly perpetuate it.

Haitian hustlers here are eager to subject themselves to the tourists’ patronage in exchange for free meals, gifts and cash. Their dependency is reminiscent of third-world women practically throwing themselves at GIs in Vietnam/Korean war flicks. Those women’s American dreams reaffirm notions of Western superiority. Since men typically assume the roles of providers to whom women naturally cling both on and off screen, the scenario’s gender reversal in Vers le sud underscores racial and class disparity. Another sharp contrast is the fact that Legba shows no inclination for pursuing life, liberty, and happiness in the States.

Ellen’s maternal instincts take over, and Legba becomes her charity case. He eventually flares up and tells her, “You’re not my mother.” His reaction repudiates a certain liberal view that the underprivileged necessarily welcome attempts to inculcate instill in them the supposedly higher living standards and loftier values of their benefactors. This kind of humanitarian bent generally appears to be something noble, from the documentary Born into Brothels to the dramatic The Interpreter. Still, the efforts can seem patronizing all the same. Only a few films, like Manderlay and Vers le sud, actually address how these initiatives backfire when well-to-do protagonists fail to recognize the full scope of problems or the repercussions of their actions. In instances involving third-world deprivations such as the one here, there is always some subconscious colonialism on the part of the first-world protagonists in presumptuously appointing themselves saviours.

Cantet’s film addresses its characters’ remorse over the poverty in Haiti as well as the self-serving motives behind their charity. Attention from the irresistible Legba is the tonic that boosts Ellen’s ego, but she only asks him to join her in Boston after he gets in trouble. And viewers can safely conclude that black men ultimately don’t fit in her scene back home. Most other films entitle their protagonists to this kind of self-absorption instead of examining it. The Constant Gardener is about personal mission, global conspiracy, and inflicting liberal guilt onto viewers by depictions of a poor and unruly Africa, and it broaches the outrageous events in Kenya only to embellish the magnitude of the corporate villain’s callousness and the saintly martyrdom of Rachel Weisz’s character Tessa. Its protagonist (Ralph Fiennes) hardly interacts with the Kenyan populace at all.

Vers le sud is not without its flaws. It occasionally seems like a poor imitation of a poor film, Casa de los babys, which has a group of American women in Mexico looking to adopt orphans. Like Sayles, Cantet tells the story through the dissimilar perspectives and experiences of a diverse group of characters in a very precise setting. But instead of gracefully shifting through the various viewpoints, he and co-writer Robin Campillo devise first-person confessionals—complete with title cards—with the characters directly addressing the camera. In a monologue both titillating and repulsive, recently divorced Southerner Brenda (Karen Young) tearfully recounts propositioning the then 15-year-old Legba and reaching her first orgasm at the age of 45 during her first visit to Haiti with her husband three years previous. While at times revealing, these vignettes are redolent of something from an amateurish daytime-TV movie of the week.

Albert (Lys Ambroise), maître d’hôtel at the beach resort where the ladies stay, is the only Haitian character with a narrative voice. His father fought against the first American occupation in 1915 and told him “white men are lower than monkeys.” Albert observes the skin trade from a much different angle than the tourists. He asserts that dollars are far more damaging than cannons, and his trepidation turns out to be quite prophetic. Although the film primarily concerns the tourists’ narrow point of view, the omission of Legba’s narrative voice is incomprehensible considering that Albert gets his say.

With Ressources humaines (1999) and L’emploi du temps (2001), Cantet has established a reputation due to his penchant for the clash between professional and personal identities. Both films address the modern phenomenon of corporate downsizing in his native France and its complications on personal and family lives. But his latest signals a deliberate change of pace: This first try of his at a literary adaptation tackles three short stories by Haitian-born author Dany Laferrière that bare no resemblance to the milieu of the director’s previous work. The only connection here to his past thematic threads is the fact that Legba’s professional life is almost illusionary, and his reality outside the resort is harsher than any of his benefactors can imagine. It recalls Aurélien Recoing’s character Vincent desperately keeping up the appearance of employment in L’emploi du temps. But Vers le sud isn’t Legba’s story at all.

Cantet illustrates Haiti with a neutral approach, without fashioning it as some sort of dangerous, savage land as Meirelles did with Nairobi in The Constant Gardner and Rio in City of God. Still, Vers le sud almost trivializes its devastating historical and political backdrop. Perhaps reflecting the tourists’ naiveté and the resort’s insular nature, the film references atrocities only in passing (a cop bullying a street vendor, a mention of the lavish nightly feast at the presidential compound, an unfathomable assassination). Cantet’s previous features show he’s capable of more complex context and richer characters. With its moral ultimately turning out to be something as trivial as the prologue’s contention that everyone necessarily wears a mask, the film has unfortunately missed the mark amid weightier and worthier subject matter.

From Cinema Scope No. 25, Spring 2006. © Copyright 2006 Martin Tsai. All rights reserved.

February 17, 2006

Freedomland

Directed by Joe Roth Starring Samuel L. Jackson and Julianne Moore

Reviewed by Martin Tsai

Hollywood types have their minds on race relations these days, as evidenced by the emergence of Crash as a bona fide Best Picture Oscar contender. Clockers author Richard Price’s novel Freedomland, which revolves around a white kid gone missing in the projects and the ensuing racial discord, is receiving opportune big-screen treatment. Under the direction of part-time helmer/fulltime studio honcho Joe Roth, the film feels like a generic whodunit attempting to pass as a weighty Spike Lee joint or a Jonathan Demme social weepie.

It’s every parent’s worst nightmare and then some: Her four-year-old son was sitting in the back seat when a carjacker sped off with her vehicle. Brenda (Julianne Moore) describes the perpetrator as a black man, thus leading to a standoff between the residents and the predominantly white police force. Det. Council (Samuel L. Jackson) knows his way around the ’hood, and tries to stem a potential riot while sleuthing for a suspect and the missing child. But Brenda’s hotheaded cop brother Danny (Ron Eldard) interferes with Council’s investigation and intervention while also betraying her shady past.

Originally slated for a late-’05 release complete with a campaign built around Moore’s central performance, the film ultimately sat out the crowded awards season. Moore is indeed powerful, but she does little to salvage this generic and rather unconvincing mystery halfheartedly dressed up as social inquiry. The film ponders racial profiling and police brutality every time its plots stall. While its take on race is more substantial than the parade of animated caricatures in Crash, Freedomland still comes off as inconsequential due to its laughably absurd resolution.

© Copyright 2006 Martin Tsai. All rights reserved.

January 27, 2006

Imagine Me & You

Directed by Ol Parker Starring Piper Perabo, Lena Headey and Matthew Goode

Reviewed by Martin Tsai

Gay cowboys aren't the only ones who wish they knew how to quit each other. Apparently so do "dygetarians" AKA "lesbifriends", as alleged in the Brit rom-com Imagine Me & You. These homos can only be happy together behind the backs of their hapless spouses. On her walk down the aisle to marry gormless stiff Heck (Matthew Goode; no, not the rocker), Rachel (Piper Perabo) and floral designer Luce (Lena Headey) exchange goo-goo eyes. Luce yearns for Rach to come to her window while everyone else obliviously tosses off obligatory gay jokes, i.e. "she's gay as a tennis player". Rach is soon thinking about the girl she loves day and night, and inevitably faces the dilemma of whether to follow her heart or … really, what else would anyone follow in this post-1963 day and age?

Imagine is like When Night is Falling as re-written by Richard Curtis. Every character speaks with that toffee-nosed Hugh Grantish sarcasm. There's the ghastly wedding scene complete with embarrassing speeches and the wankiest pop oldies, à la Curtis's Four Weddings and a Funeral. By the way, can we please annul all this unholy movie matrimony. Wasn't Nia Vardalos's ethnic nuptial circus more than enough? Anyway, Imagine is full of cute foreshadowing and clichéd coincidence (for example, Rach rings Luce and hangs up without saying anything, then Luce hits the redial button and wouldn't you know that poor Heck answers). Really, how much pride, prejudice, sense and sensibility are we supposed to stomach?

Bottom line is, Imagine lacks the charm supplied by Grant or Colin Firth. It doesn't even have cowboys doing the Jack Twist (or Jack Nasty if you will). Exactly a decade ago the Wachowski brothers made Bound, which had a similar setup except the married woman got her lesbo lover to steal from the husband. Bound is arguably one of the best gay-themed films because sexuality is completely irrelevant to the plot, and the queer characters are no different from regular folk. The essential problem with the likes of Imagine and Brokeback Mountain is that they are gay films made by heteros for heteros. They purport to be sympathetic toward homosexuals, yet unwittingly cast them into the stereotype of selfish home wreckers. These films are exploitative if not downright fraudulent.

© Copyright 2006 Martin Tsai. All rights reserved.